The general concept of pressure

Some might remember the definition of pressure from a Physics course. Pressure is a numerical expression of the effect of a body on a square meter of surface, which is expressed in units of "p" (Pa).

The calculation formula is written as follows: p = F/A, where «F» is the force and «A» is the area. The equation can be written a little differently 1 Pa = 1N/m2 (N is the Newton unit).

The meaning of this is that the pressure per unit area increases with increasing force or with decreasing area. You should remember these two things as we will come back to this again.

There are many nuances in sharpening and beginners make mistakes. Excessive pressure is one of the most common ones, along with not spending enough time to sharpen, selection of the wrong angle, selection of a too coarse abrasive, and failing to maintain abrasive hygiene.

Pressure in sharpening

Sharpening as a process is a set of steps designed to give a knife the ability to cut if it is untreated or dull.

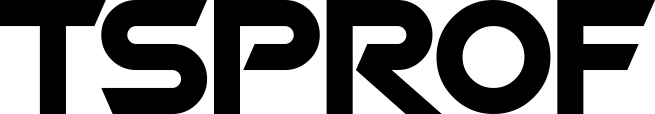

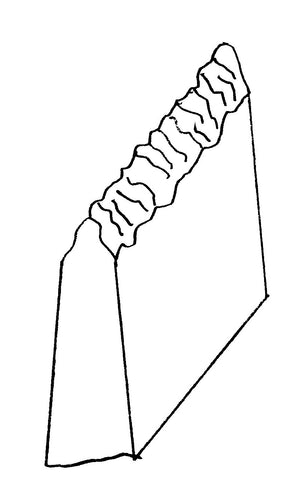

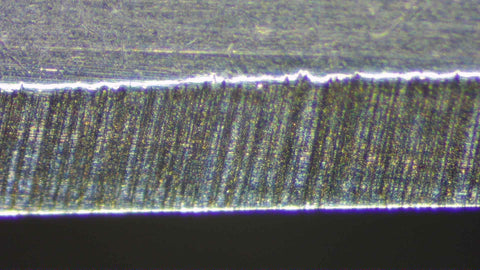

Image. 1 Dull blade

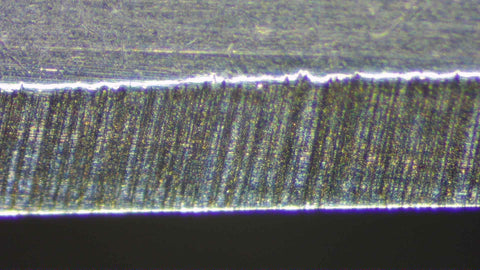

During profiling with a coarse abrasive and sharpening with a finer abrasive, removing metal can leave scratches and grooves.

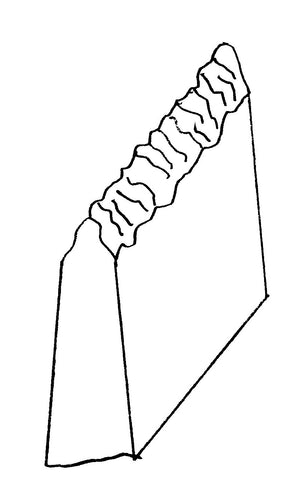

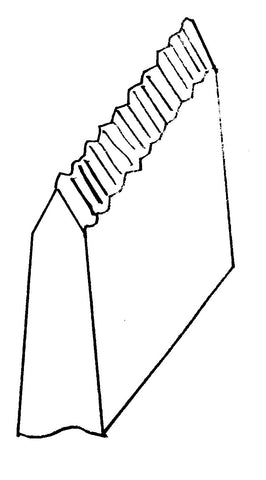

Image. 2 The blade after profiling with a coarse abrasive.

You will straighten out and fix all irregularities on the metal surface during the next stage - finishing.

To understand exactly what is happening on the cutting surface when you put pressure during sharpening, you need to pay attention to the way the bevel looks like or check the result with a magnifying glass with a large magnification factor.

During sharpening, the contact of abrasive with steel and mechanical impact causes plastic deformation in the surface layers of the metal due to dynamic loads. Micro-volume structural changes on the surface of solid objects during contact are closely related. You could also say that the abrasive and the blade steel adapt to each other. There is an acceptable range of loads for each of the materials.

You can tell the compatibility of a particular abrasive with a particular type of steel by examining how they work together. Meaning that the abrasive bar removes a certain amount of steel, followed by a certain sound and tactile response that you can feel on the knife blade if you sharpen manually. If you use a sharpener, you will feel this going through the abrasive holder and then into your hand.

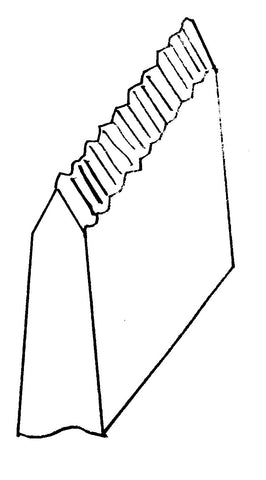

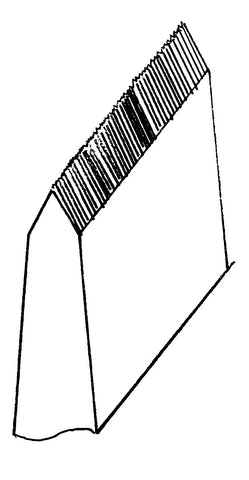

Image. 3 Blade after sharpening with a finer abrasive sharpening stone

In the best case scenario, the abrasive should gradually and carefully remove the steel without jolts. This is what proper abrasive compatibility with steel means. This is what they call sharpening. In the future, if the sharpening stone starts to slide, you will need to refresh its surface or change the whole stone.

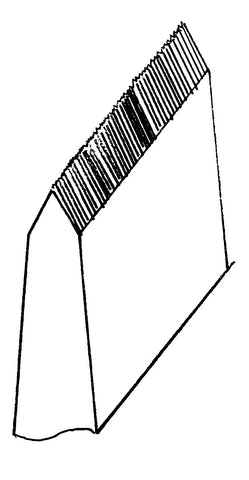

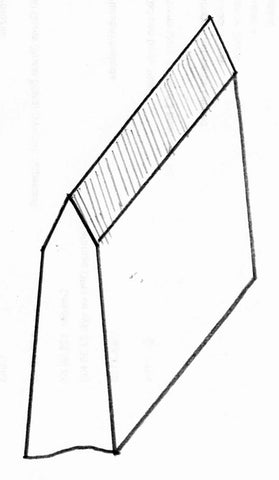

Image. 4 Blade after finishing

With further finishing, the surface of the steel gets harder and less ductile at the micro level. Excessive hardening can cause particles to separate from the metal surface and with too much pressure this can lead to unwanted scratches and and cause further destruction of the cutting edge.

Image. 5 Uneven scratches

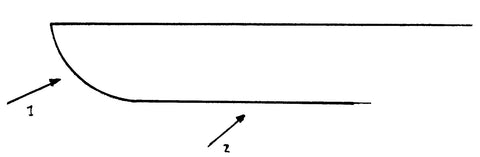

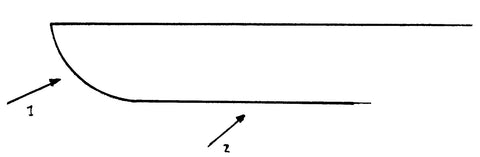

Example: the weight and pressure of the bar at the point of contact per square millimeter on the flat area of the blade is less than that on the belly, so you have to be especially careful during the finishing stage.

Image. 6 Areas of different pressure on the cutting edge: 1 - belly area with high pressure and 2 – blade flat with lower pressure

The fixed angle guided sharpeners have a much lower pressure, compared to hand sharpening, so you only need to hold and move the abrasive holder, while the stone works.

Mechanical impact of excessive pressure on secondary bevels and cutting edge

The increased pressure causes metal particles to stick to the surface of the abrasive bar and fill its pores, which leads to clogging and a noticeable loss of efficiency of the sharpening stone.

Image. 7 Clogged sharpening stone

On top of that, abrasive grits can dig into the surface layer of the metal of the blade, which can lead to its destruction.

Excessive pressure, if you use an abrasive that is too coarse for the initial stages, can lead to deep singular scratches or grooves, which are often difficult to remove with a finer abrasive and can lead to chipping or pitting after sharpening. The reason for this is that in some steels the carbides are spaced so far apart that they get worn away by the abrasive grits.

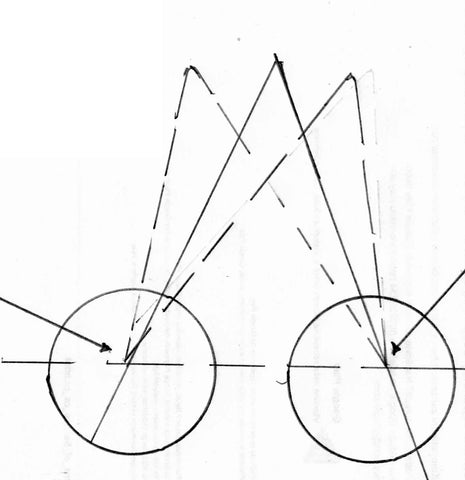

Besides this, you will find a burr raising and due to its removal during the cutting edge preparation stage, the edge may chip.

Even if you have removed the burr, applying too much pressure or increasing the angle can cause the apex of the cutting edge to lean to one side or the other.

Image 8 Point of pressure at the micro level: 8.1 Point of side impact, 8.2 Possible change

Chips and micro-cracks can lead to corrosion, as there is no such thing as completely stainless steel.

Abrasive impact on steel, including sharpening, converts the impact into heat energy, which is transferred to the blade to a greater extent, because metal is a better heat conductor than the abrasive bar.

Temperature and chemical impact on steel when there is too much pressure

When you increase the pressure on the abrasive on a small contact area, the temperature of the blade and the abrasive increases and the abrasive strength of the sharpening stone decreases. Here you can distinguish two types of temperature impacts as a result of such contact:

-

contact temperature and

-

heating temperature of the secondary bevel and cutting edge surfaces

The worst thing you can do to a knife blade is to sharpen with a belt grinder. Although there is virtually no pressure, there is a prolonged friction that raises the temperature of the knife blade. If you can see sparks, you can be sure that the temperature of these particles is about 10000C or higher. This can cause differential tempering of the steel as heat transfers to a thinner part of the blade at the cutting edge, not critical only for high speed steels. The use of special cooling equipment and setting low speeds will make sharpening with a grinder relatively easy, but will require additional costs and experience on the part of the user.

It is difficult to accurately measure and record these two factors at home. The point of contact with the bevel at the beginning of work is so small that there are no devices that can truly measure this. With any abrasive, tiny sparks can form upon contact with steel and their peak values are quite high.

Theoretically, checking the secondary bevels temperature is more relevant for cyclic sharpening, for example with a kitchen electric sharpener. However, household laser thermometers are not equipped with a highly concentrated beam of light and the blade looses temperature during the time it takes for the laser beam to hit the secondary bevel and does not give an accurate temperature at the cutting edge itself.

We are not talking about the blade staying at the tempering temperature for a long time, or reaching this temperature at all, but high temperatures can assist the abrasive particles in entering the bevel's surface and/or affect the chemical processes on the surface of the steel. Some metals can form carbide oxides at high temperatures, which in turn may result in reduced stability and wear.

For example, the tungsten and cobalt oxide formation can happen at a temperature of about 5000C, and the reaction with acids and alkalis even at a lower temperature of about 900C.

To avoid excessive heating of the blade and to improve the abrasive properties of the sharpening stone, it is necessary to use cooling liquids during sharpening, which you should choose depending on the type of abrasive and steel of the knife blade.

In terms of abrasives, you have to pick the right hardness and porosity of the stone according to your experience.

Conclusions

There are various mechanical and thermal phenomena that seriously affect the quality of the surface of a knife blade during sharpening.

Due to excessive pressure and growing friction forces, especially with a small contact spot, the ductility of the steel may change due to increasing temperature, leading to deformation, chipping and pitting of the cutting edge.

But the key question is how much pressure to apply when sharpening a knife.

The pressure on the cutting edge when sharpening the knife must be adequate, because without pressure there will be no sharpening. .

Regardless of the pressure, the stone should produce results depending on its condition.

Sharpening hides many different aspects and nuances, and therefore you should do your own sharpening experiments to gain experience, which will help you make the right decisions in the future and follow the right sharpening technique.

Pressure is also one of the important nuances of sharpening with guided manual sharpening systems, such as TSPROF Pioneer. This sharpener is milled from a single block of a 7075 T6 aircraft grade aluminum and comes with 5 diamond plates, ready to make your knives razor sharp. Experience professional sharpening with TSPROF.